July 16, 2015

Continental Drifters Expanded Liner Notes

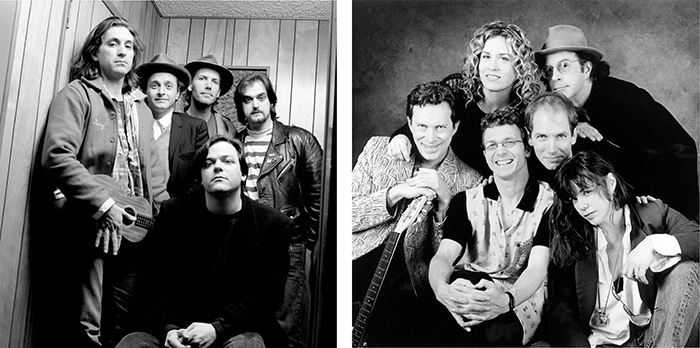

Early Drifters (left–right): Gary Eaton, Danny McGough, Mark Walton, Ray Ganucheau, Carlo Nuccio (photo by Greg Allen).

Later Drifters (left–right): Robert Maché, Vicki Peterson, Russ Broussard, Mark Walton, Peter Holsapple, Susan Cowsill (photo by Rick Olivier).

In an eventful lifespan that lasted just over a decade, the Continental Drifters created a relatively small but consistently magnificent recorded legacy, while playing live shows that generated treasured you-had-to-be-there memories for just about anyone who ever saw the band perform.

No fewer than ten musicians recorded as members of the Continental Drifters, while countless more friends, relations, and fellow travelers shared the stage with the band at various times. By the time the Drifters ceased to be a going concern, only one member—bassist Mark Walton—remained from the outfit’s 1991 founding, with a diverse yet complementary array of distinctive singers, players, and songwriters passing through the ranks in the interim.

Despite the Continental Drifters’ ever-evolving personnel, each of its incarnations shared a knack for catchy, heartfelt songwriting, as well as a powerful sense of community that manifested itself in the band’s organic, emotion-charged vocal and instrumental interaction. Those qualities were reflected in spades on the three studio albums that were released during the Drifters’ existence, and in the unpredictable, uplifting live shows that left a deep impression upon anyone who witnessed them. And while each member possessed an impressive musical resume prior to joining, the act’s image as a supergroup missed the point.

Rather than attempting to chronicle the Continental Drifters’ entire unruly history, this package focuses on two distinct aspects of the band’s body of work. Disc One documents the Drifters’ early years in L.A., collecting unreleased and rarely heard demos, and studio rarities, plus the contents of the group’s elusive 1993 debut album.

The latter originally went unreleased as a result of the aforementioned lineup shifts; it saw a limited European release a decade after its creation, yet has remained largely unheard by American fans. For listeners hearing it for the first time, and for those who were not present on Tuesday nights at Raji’s for the band’s now-legendary early gigs, this belated introduction to the original Continental Drifters will come as a revelation.

Subsequent, and more familiar, Continental Drifters lineups are featured on Disc Two, which offers a scintillating sampling of the vintage cover tunes that often graced the Drifters’ live sets, while going largely unrepresented on the band’s albums. Alongside those memorable ’60s and ’70s pop and soul interpretations are the contents of another import-only release: the 2001 EP Listen, Listen, the Drifters’ valentine to English folk-rock institution Fairport Convention and its seminal singer-songwriters Sandy Denny and Richard Thompson.

In addition to filling in some crucial gaps in the Continental Drifters’ catalog, this set serves as an expansive testament to the brilliance of a one-of-a-kind band whose timeless creative spirit continues to resonate as strongly as ever.

June 2015

Carlo Nuccio: In 1991, I was living in L.A., playing with a lot of different people as a hired gun, and writing songs and not doing anything with them. My buddy Ray Ganucheau, who I’d played a lot with in New Orleans, had just moved to L.A. to work for Microsoft.

Ray Ganucheau: I’d played music with Carlo in New Orleans in various situations. Before I moved to L.A., I’d been living in Dallas, and I ran into Carlo when he came through with the Circle Jerks. I told him that I was thinking of moving to L.A., and if I made it out that way, did he want to play some music together?

Mark Walton: I first met Carlo when he was The Dream Syndicate’s drum tech, and after that, I played with him in a bunch of bands in L.A. He was a great drummer, but then I heard him sing, and he was really good. Carlo told me that he had a friend who’d moved to town who was a great guitar player. And then Gary Eaton was playing a gig, and his band couldn’t make it. So, he asked Carlo to fill in, and I happened to be in the room, so Carlo suggested me. We really enjoyed playing with Gary, and he had some cool songs, so we brought him into our thing.

Gary Eaton: I became buds with Carlo after we played together in a cowpunk band called the Devil Squares. Carlo liked the songs that I was writing for the Devil Squares and the Ringling Sisters, and told me that he was putting something together with Mark and Ray, and he invited me over to Ray’s house to jam with them.

Carlo Nuccio: Being from New Orleans, I never got the whole spandex thing that was going on in L.A. at the time. All these junior rock ‘n’ roll stars walking around with big hair and sticks in their back pockets. It was a weird time in L.A., and I kind of felt like a relic there. I like a lot of genres and I’m excited by a lot of different kinds of music. I really liked playing with Keith Morris when we did Buglamp, just blazing through songs. I’d just done the Tori Amos record, and then Mark and I went on the road with Carlene Carter. In that environment, you have to be a chameleon to survive. On the other hand, I also played with guys like Pat McLaughlin, and what I really loved was American music, where the song has some sort of elasticity and it’ll still make sense in 20 years. Ray and Mark and Gary and I all liked timeless music at a time when nothing seemed timeless.

Ray Ganucheau: It started out as a casual thing, but it was obvious that we were all on the same page musically. A big part of the concept was that everyone would be able to bring in their own songs and sing them. And Carlo and I had been writing some songs together, including “The Mississippi.”

Carlo Nuccio: Not a lot of thought went into it at first, but we realized pretty quickly that this was a good deal. It was a weird time for music in L.A. Singing and songwriting had gone out of fashion, and I think that we were all feeling a longing for real songs and real singing. We all wrote pretty down-home stuff, and we were all pretty like-minded about music, so everything fell together pretty quickly.

Mark Walton: We didn’t start with the intention of it being a serious band. To me, it was just a fun way to play music with people that I liked and who had similar ideas about music. We just started playing, and the sound evolved out of that. After playing with The Dream Syndicate and Giant Sand and being involved with the whole alternative world, it was nice to play with musicians who had a different take on music. And it was a much a social thing as a musical thing. Ray was just about the only person I knew who had kids, who was responsible and had a real job. He and his wife and kids were just so sweet and nice, and we enjoyed hanging out with them, making gumbo and telling stories.

Carlo Nuccio: A lot of it was centered around food and drink. Mark and I had a place up on Buena Park Drive, which Susan and Vicki later dubbed the “batch pad,” and we’d get together there or at Ray’s place. I don’t think we ever did any electric rehearsals; it was just the four of us sitting on the couch with acoustic guitars, running the songs down, and working on vocals and stuff. Every guy had already accumulated a bunch of good songs, but they were never as good as the ones that were conceived when we were playing guitars on the couch. The chemistry was undeniable, and it was reflected in how the songs would always end up sounding like the Continental Drifters.

Gary Eaton: The chemistry was always there, and there was never a lot of explaining necessary. In my other bands, it could be a struggle to get people to learn new songs. But with the Drifters, I’d show them the chords, we’d count it in, and bam, the song would be there. The arrangements would write themselves. I’d never experienced anything like that before, and it was revelatory. And it had always been a challenge teaching people harmonies, but with the Drifters, you’d go into a rehearsal, and Ray and Carlo would just knock out the harmonies effortlessly. It was mind-blowing to me. It’s the way music should always be, but isn’t.

Ray Ganucheau: Carlo and I had always liked the name Continental Drifters, which had been the name of a New Orleans band that Carlo had been in with Tommy Malone, John Magnie, and Johnny Ray Allen before they formed The Subdudes. Carlo called John Magnie from my house to ask if he could use the name, and Magnie said, “Sure.” I think he sent us one of their old banners that they used at their gigs.

Mark Walton: We had been sitting around at home playing casually and thinking “Wow, this sounds great; we should do a gig.” So, we booked a one-off show at Club Lingerie, and that went really well. By then, we had added Danny McGough on keyboards. We liked Danny a lot; he had a band called 7 Deadly 5, which opened for us several times at Raji’s, and Carlo knew him, because he’d been playing keyboards with Peter Holsapple’s solo band.

Danny McGough: I had played with Carlo in a band called the Swingset. We wanted to be a soul band, and we just loved New Orleans. Carlo grew up with all that stuff and really knows it to the depths. One day Carlo says he’s starting a band called the Continental Drifters and invited me to play keyboards.

Carlo Nuccio: The Club Lingerie gig ended up being a pretty good night. From there, it was “OK, what do we do now?” I was the house engineer at Raji’s—that was my make-ends-meet gig—and had booked some shows there, and I had played every Tuesday night with the Billy Bremner band. The place had changed management, and Billy had dropped out, and the new guy was shocked because the place wasn’t doing well. So we took Tuesday nights, and Raji’s became the Drifters’ base. We went to Kinko’s and made one big poster and put it up on the wall—it was me, Mark, Ray, Gary and Dan McGough with “every Tuesday” written on it. We put it up high so nobody would rip it down, and it stayed there.

Mark Walton: We played every single Tuesday night of 1992 at Raji’s, except for one night when I couldn’t rally enough people for a band. We had just recorded our first demo, so instead of us playing, I handed a copy of our demo to whoever showed up at the door. Without the Raji’s residency, we wouldn’t have been a band. We’d play four, five hours, pretty much until they turned out the lights. We chose Raji’s, because that situation fit the way we saw ourselves as a band. They let us play whatever we wanted, and they let us keep 100 percent of the door and drink as much beer as we wanted, so we were happy. It was more like our own private party than a regular club gig, and you never knew what was gonna happen.

Ray Ganucheau: Developing the songs in that live, spontaneous atmosphere definitely influenced the way the band evolved. The band became a living organism, and took on its own personality. There wasn’t a leader, and no one was in control. It just sort of moved forward spontaneously and evolved on its own terms.

Gary Eaton: There were a few other bands around L.A. at the time who were kind of rootsy, but we loved a lot of different kinds of music. So we could go from sounding like The Band or NRBQ, to sounding like a pop band or a punk band a minute later. I got to a point where I was sloughing off on all of my other projects, because the Drifters was so much more satisfying. Those Raji’s gigs were great, and I felt like a big shot, just because it was so good. Playing with Carlo really brought me a lot of joy; he could read a song before it even came out of you. And Ray was such great guitar player and so supportive and easy to work with. It was always great looking over at him and getting a nod.

Mark Walton: Raji’s was our incubator, and it was great to have a place where we felt comfortable and where we were allowed to do what we wanted. Some of the bigger clubs offered us bigger gigs, but we said no. We didn’t want to be part of that Hollywood music machine, that wasn’t the purpose of it. The purpose was for us to have a good time. If it went great, it was great. And if it didn’t, we still had a good time.

Carlo Nuccio: The backlots shut down over at the studios, and the actors would come. People would load in and get their Budweisers, and we’d back up whoever we’d back up, and then we’d take five minutes and walk on stage, and the whole show would wrap by 12:20. I don’t think the door was ever higher than eight or ten bucks. Nobody was doing residencies in L.A. at the time, but people knew that we would be there every week, or that some version of us would be there.

Mark Walton: On some nights, somebody wouldn’t be available, or one or more of us would be out on tour with another band. So we had a great bench of auxiliary Drifters who could fill in. When I was on the road, Micki Steele from the Bangles would sub for me. Everybody had at least one sub on the bench—Robert Maché or Dave Catching or Kevin Jarvis or John Convertino—but somehow it would always come out sounding like the Drifters. One Tuesday night I had just gotten back from touring with Carlene Carter, and I didn’t tell anyone I was back in town yet. So I snuck into Raji’s and I got to see the Continental Drifters.

Robert Maché: I had originally met Mark at an audition for Steve Wynn’s band. I got that gig despite the fact that I fell asleep at the audition, and I ended up playing with Mark in Steve’s band for two or three years. Mark became my brother, and my roommate on the road. Mark was the best man at two out of three of my weddings, and I was the best man at his wedding. I started sitting in with the Drifters at Raji’s as half of the “Bob and Bob show,” which was me on mandolin and Robert Lloyd on accordion. We played on “Karen A.” and “The Mississippi.” I think that all of us were aware that something special was happening at Raji’s. It was the sort of thing you’d always want to happen, but which doesn’t happen if you tried to make it happen. You would get into Raji’s and it would be fun before anyone even started playing. The vibe was electrifying, and it was the loveliest compliment to be asked to be included in this thing.

Steve Wynn: I spent many a Tuesday night at Raji’s watching the Continental Drifters—just about every week, in fact; I’m sure I saw them play live more than any other band. I was drawn in at first because of my old Dream Syndicate bandmate Mark Walton, and because Raji’s was pretty much the coolest club in the coolest location. Every Drifters lineup was great, but that first one was a revelation, because at the time, the idea of a band that had not one but three incredible singers and songwriters was a pretty novel thing in our little indie-underground Hollywood scene. I ended up writing and recording with every one of them, except Ray. Ray was the one I knew least well, but he had a voice that would stop you dead in your tracks. But the thing was that they were all that good.

Carlo Nuccio: We started backing other people up pretty early on. It started with our friends, like Steve Wynn, Victoria Williams, and Syd Straw, and eventually we had people like Jackson Browne wanting to do it. It got crazy, but it was really fun, and learning all this material and playing with all these people was a big education for us. We’d invite our weekly guests up to the batch pad to work out material for the next show.

Steve Wynn: Those guys were so great when they were playing their own songs, and then they would turn around and be the best backing band in the world for whoever might have dropped by that week, including yours truly. I could always jump on stage with them and know that I could choose from several dozen of my own songs, or just about any Dylan or Neil Young song. Actually, the last time the Dream Syndicate played together for over 20 years was at a Tuesday-night Drifters show. It was Dennis’ birthday and Mark, Paul and I decided to surprise him by meeting up at Raji’s, and midway through the evening we walked up to Dennis, handed him a pair of sticks and told him it was showtime. We hadn’t played together in several years and it was a blast.

Danny McGough: Peter Holsapple had just gotten done with his R.E.M. gig and would sit in with us more and more on Tuesday nights. I’d set the piano up on one side of the stage and the organ and Leslie on the other, which made for a pretty crowded stage. And Susan Cowsill and Vicki Peterson started coming around and singing and were great. They both always sounded like hit records walking.

Peter Holsapple: The dB’s had broken up, and I had quit R.E.M. the day they got their Grammy for Out Of Time. Carlo, who I’d known from New Orleans, said that I should come and hear his band—and they were great. Then Carlo said that Ray was gonna be out of town, and asked if I and our friend Dave Catching would sub on guitar that night. That was fun, and I came down and sat in a bunch more times. Then Carlo told me that Danny was going off to do something else, and would I like to join the band? I wasn’t looking to join another band, but I said that I’d love to try producing them.

Mark Walton: The first thing that we recorded was a three-song demo: “The Mississippi,” “Karen A,” and “Green.” I think we also recorded a version of “New York” during those sessions. Danny was still in the band, and he played on that stuff. Peter produced it, and Susan and Vicki sang on “The Mississippi,” which became the A-side of our single on the Singles Only Label. The B-side, “Johnny Oops,” was from a live show in New Orleans. Eventually Peter agreed to join the band. He had been sitting in with us just about every Tuesday and was really enjoying himself. Danny was too, but Peter seemed to have a stronger connection to what we were trying to do.

Danny McGough: I never really felt like a full-fledged member of the band, more like a guy that sat in with them and was friends with them. I still had 7 Deadly 5 going and was doing sessions and live gigs around town at least three nights a week. Carlo called me up to say they didn’t need two keyboard players anymore, and I was fine with that. It felt like the right thing—until two weeks later when they opened for Bob fuckin’ Dylan at the Pantages! 7 Deadly 5 still opened some of the Raji’s shows for a bit after that.

Peter Holsapple: I agreed to become a Drifter, but I said that I didn’t want to play guitar, and I didn’t want to sing. I just wanted to play keyboards and get really good at that. I felt like I’d been such a disaster as leader of the dB’s after Chris Stamey left. So I liked the idea of joining a group like the Continental Drifters, which already had great vocal and instrumental prowess, and which would allow me to hone my keyboard skills and not have to worry about the other stuff. My job description changed as time passed, but at the time, I was happy to keep a low profile.

Ray Ganucheau: Peter added a lot to the band when he joined fulltime. He had such a big musical knowledge base, and he was such a versatile player and singer. He also knew a ton of people and was always introducing us to new singer-songwriters and people who’d come and play with us. And his studio experience was a big help when it came time to do the album.

Vicki Peterson: I remember running into Mark at Uncle, the rehearsal studio that he and his brother ran, while I was briefly playing with The Cowsills. I hadn’t seen him in years, because I’d spent most of the ’80s touring with The Bangles. Mark said I had to come to Raji’s and see this band, the Continental Drifters. A week or two later, I went with Susan. We were performing as The Psycho Sisters at that point, and we just fell in love with this band. We sat in the back of the club and said, “OK, how are we gonna get these guys to be our band?” Soon afterward, we started getting up to sing backups with them and became part of the Drifters auxiliary club.

Susan Cowsill: I think I became aware of the Drifters when my brother Barry brought Peter to a Cowsills show. Then Vic and I went to Raji’s, and we both became gigantically smitten. I think the first Drifters thing we learned was the backgrounds to Gary’s song “Dallas,” and after that, every other member said “I’ve got this song, what have you got for this?”

Robert Maché: I love Vicki and Susan’s story about having a special place on stage, off to the side, where the bass would vibrate that part of the stage so hard, and they would sit there with big grins, like two girls sitting on the washing machine during the spin cycle.

Vicki Peterson: I had never seen anything like them. The songwriting was so good and the performances were so incredible. It seemed like every original they sang was a classic old country song, or an unknown song by The Band. I had never seen a band where the cover songs were so well integrated with the originals, and their songwriting was so high-quality that the covers didn’t overshadow the originals. Their covers played a huge part in who they were and how they presented themselves.

Peter Holsapple: It wasn’t uncommon to see the Drifters at Raji’s and hear three or four songs that you would never hear again. Or maybe we’d do the same songs as last week, but they’d sound completely different. You never knew who was gonna have a moment of inspired genius. After the stress that I’d always associated with being in bands, this was a whole new experience. I was used to playing with strict timekeepers, so having Carlo doing all his loose New Orleans stuff was liberating. And Mark played these big, swooping condor bass lines, and you’re always asking yourself how he’s gonna land. In some ways, our sets were like early aviation attempts. Is this thing gonna take off? Is it gonna land? Is it gonna crash? Is the wing gonna graze the building on the way down? We were fine with the chanciness of it all, because even when it wasn’t perfect, it was powerful. The dB’s were always slaves to our demos, but the Drifters were not the opposite of that. The Drifters were about learning the song and making it as good as it could be.

Brett Milano: The thing I remember most is the “Tuesday night social club” feel of the Raji’s residency. Raji’s was kind of a dump, but it was our dump. It had the bar in the front room and the cozy music room in the rear, with the tamale concession that everybody tried once. It felt that we were catching a soon-to-be-important band at its inception, like we were seeing the International Submarine Band back in the day. It didn’t hurt that all of the band were lovely folks who encouraged a family vibe with the audience. There were always lots of singalongs toward the end of the night, and requests getting shouted out. Part of the mystique was that they were a piece of New Orleans that had somehow landed in Hollywood. Carlo was a real larger-than-life character; he could play absolutely in the pocket and then fall off the drumkit afterward.

David Jenkins: Brett and I started hanging at Raji’s every Tuesday night. As a musician, what I had always looked for was a sense of musical community and likemindedness, and I found that and much more at those shows. Beyond the power of those voices and that music, the thing about Tuesdays at Raji’s is that it instantly accepted us and bonded the listeners and players. The sets always changed in the mixture of originals and covers, the band members would change instruments now and then, and you never knew who was going to show up and sit in. The fluid nature of the band made it all seem totally natural.

Peter Holsapple: I think that the impetus for the Drifters to start recording was that we realized that you can only play Raji’s for so long, and that we had to start doing things so that more people could know about us. For the album, we went into the studio with me producing and Mark McKenna engineering. I was a member of the band by that point, but I still didn’t want to be the lead singer on anything, so I had Gary sing my song, “Invisible Boyfriend.” I did play some mandolin and guitar on the album, including my terrible attempts at pedal steel on “Mr. Everything.” I tried to do that before the rest of the band got to the studio, so they wouldn’t see me struggling to record the part a note at a time.

Ray Ganucheau: We cut the tracks at a place in Glendale, and then did some more recording and overdubs at a little studio in Santa Monica called Mad Dog; then Peter took it to Bearsville Studios and mixed it there. I think it’s a pretty good snapshot of what the band sounded like at the time. It wasn’t as loose and as spontaneous as our gigs were, but the spirit of it is there.

Vicki Peterson: I can’t remember if there was ever an actual conversation about Susan and I joining the band. My memory is that it was an organic transformation, and it wasn’t something we were particularly angling for.

Susan Cowsill: The whole thing escalated pretty quickly. I was dating Peter; Vicki was dating Gary; and I was living half the time up at the batch pad. The way I remember it, we were sitting in the foyer at Uncle Studios, and Carlo said, “Well, the girls are obviously in the band.” And I remember Vic and I looked at each other and went, “Uhhh, did we miss a memo?” But at the same time, I guess we kind of knew it. It was perfect timing. Vicki had just de-Bangled; I had just ended my relationship with Dwight Twilley; and we were both emotionally ripe for a whole new life to happen.

Vicki Peterson: The band was a refuge for me, as it was for most of the people in it. I was still coming off the dissolution of The Bangles and the death of my fiancée. I wasn’t looking to be in another band, and I wasn’t even sure that I still wanted to be in music. But the Drifters was so effortless and so welcoming and so beautiful that it became a healing force for me. It was a wonderful collection of writers and singers and humans and friends, and it was as much a social and drinking club as it was a band. For my first few years in the Drifters, I pretty much sang backup and played auxiliary guitar, and I didn’t feel the need to push myself or push my songs. It was amazing to just be able to get on stage in a flannel shirt and no makeup. All I had to do was show up, sing, and have a good time. All the un-enjoyable stuff that was ancillary to the actual making of music just didn’t exist in the Drifters.

Susan Cowsill: We’d all get together in the middle of the week at the batch pad and work up new stuff, and then play it on the next Tuesday. Most of us were recently single in one way or another, and the future was unknown, yet it was unfolding every Tuesday at Raji’s, with all kinds personal dramas and musical dramas in between. It was a big piece of life lived in one year.

Carlo Nuccio: In every incarnation of the band, everybody could sing. We all loved bands that could sing, and there just weren’t many of those around at the time. Then the girls came in, and they could really sing.

Peter Holsapple: It was always fun coming up with covers and figuring out what we could do with them, and those options expanded after Susan and Vicki joined the band. I was always sorry that we didn’t release our versions of “Tighter, Tighter,” “Dedicated to the One I Love” and “Farmer’s Daughter,” because those were pretty prominent in our shows.

Susan Cowsill: Our covers usually come out of nowhere. We’d be in a rehearsal, and somebody would hit a riff, and somebody would go “Yeah,” and everybody would magically know exactly what their part is, what the harmony is, what the bass line is. It was like that pretty much every time. Somebody would sing a line or play a riff, and the rest would just fall in. When those moments occurred, nobody was thinking about running a tape. So I guarantee you that, for everything that’s recorded, there’s something else that wasn’t.

Gary Eaton: To me, our version of “A Song for You,” on the Gram Parsons tribute album Conmemorativo, which is credited to the Walkin’ Tacos, is the best representation of what the band sounded like. I think that that track captures the energy and the joy that was us at our best.

Mark Walton: After Susan and Vicki joined the band, we recorded three more songs—“Who We Are, Where We Live,” “The Rain Song,” and a new version of “The Mississippi”—with the seven-piece lineup. Not long after that, Carlo and Ray started missing New Orleans, and they decided to move back.

Carlo Nuccio: It was around the time of the riots in L.A. that I decided to go back to New Orleans. I sat down with the band and said, “I can make way more money playing around New Orleans, so I’ll be able to fly wherever I have to fly to play with the Drifters.” Then Ray said he was ready to move back too.

Ray Ganucheau: I’d been living in L.A. for a while, and I had young children, so we were just ready to go back. We thought we could try to keep the band together, even if everyone wasn’t in the same place. But then Peter and Susan and Mark and Vicki decided to come along.

Mark Walton: Gary didn’t want to leave the band, but he couldn’t leave his son in Los Angeles. He was divorced and the only one of us who really had ties in L.A., and he couldn’t move. It made me sad that Gary got left behind, because he wrote good songs, played great guitar, and sang really well, and I really think he shines on the album.

Carlo Nuccio: I don’t think we expected anyone to follow us. But one by one, they came. It was an obvious move in some ways, because the first time we’d played in New Orleans, we sold out a 600-seater and they were still screaming at the end of the night. People in New Orleans got the Drifters in a way that people in L.A. didn’t. So it was an obvious move in some ways.

David Jenkins: The Raji’s show that was perhaps the craziest was the night we all dressed in drag to send off Carlo and Ray to New Orleans, with Seal, Kirsty MacColl and Steve Lillywhite in attendance. Then they all moved to New Orleans, and we lost our little hang and missed it terribly.

Susan Cowsill: Peter and I moving to New Orleans was a real Grapes Of Wrath moment, because I was pregnant and hoping to get to the orange orchard before I give birth. But New Orleans welcomed the Drifters with open arms, and it was obvious that this was where we were all supposed to be. New Orleans is like Ellis Island: bring your tired and hungry, and the band was like that too. When we got our residency at The Howlin’ Wolf, it pretty much became a continuation of what had been were doing at Raji’s. New Orleans affected the evolution of the band—and of our individual lives—to a degree that we’d never imagined. We all became New Orleanians, even after the band ended, and the only thing that tore that up was [Hurricane] Katrina.

Vicki Peterson: I didn’t think I would be moving, because I was still reeling from large life changes. But I helped Peter and Susan pack up their truck, and I drove to New Orleans with them and helped them get settled. Then I fell in love with New Orleans, which began a two-year period for me where I commuted from L.A. to New Orleans, and stayed there for months at a time, before I finally moved.

Ray Ganucheau: I continued playing with the band for a little over a year in New Orleans. Then I had some health problems that I couldn’t really overcome while remaining in the band, so I had to drop out. I really missed it, but I didn’t really have much of a choice.

Mark Walton: Gary had stayed in L.A., and Ray’s doctor said he couldn’t play with the band anymore, so we needed a lead guitar player and the logical step was to call some of the people we’d played with. We asked Robert Maché if he wanted to move to New Orleans with us and he said “Sure.” The cool part was that he already knew all of our songs because he’d played them so many times at Raji’s.

Robert Maché: When I got the call, I was living in Tucson and having the worst time of my life and thinking, “How the fuck do I get out of this?” So I was, “OK, I’ll be right there.” I commuted from Tucson for Drifters gigs for about a year and a half. That was a transitional period, because they were still figuring how they could make this work, which was resolved by them deciding that if they could get everybody in New Orleans, it would happen. And it did. After Vicki and I moved there, things started to accelerate.

Mark Walton: The dB’s’ old manager Jimmy Ford and his partner Frank Quintini had started a management company, and they wanted to manage us. But they couldn’t get us a deal for the album we’d made in L.A. Then they decided to start a label, Monkey Hill, and asked if they could put the album out themselves. But then Gary couldn’t come to New Orleans and Ray had to quit, so we weren’t the band on that album anymore. So we started recording stuff with our new lineup, and that became our Monkey Hill album. Robert was still in Tucson when we recorded it, so we sent him rough mixes, and Vicki went to Tucson and recorded all of his guitar parts there.

Carlo Nuccio: Back then, I was smoking a lot of dope and snorting as much coke as I could, and it got to the point where I was a full-blown junkie. That’s what led to the falling out between me and the Continental Drifters.

Robert Maché: No one ever kicked Carlo out. We agonized over it at great length, and we sat him down and told him that he had to choose between the band and getting high, and he didn’t choose the band.

Carlo Nuccio: When they did the intervention on me, I was like, “I’ve taken this band as far as I can take it,” which is the most arrogant, idiotic thing I’ve ever said. Eventually, I woke up, and now I’m still alive, which is a fuckin’ miracle. They had gotten somebody to play drums, and Peter asked me to come down and hear them at Carrollton Station, and I said, “You think that guy does what I do?” And Peter goes, “Well, who do we get?” And I said, “Russell Broussard, that’s the guy to get.”

Susan Cowsill: Russ could have been the most questionable choice, because he came from a whole different place musically. We knew him from playing Cajun zydeco-rock in the Bluerunners, so we had a rehearsal down at the Mermaid Lounge with the attitude of ‘Let’s see if this Cajun kid can rock.’ We played, and Russ threw down, and another wounded soldier joined the tribe.

Robert Maché: New Orleans got us. In New Orleans, all you have to do is get people together and it’s a party, because people in New Orleans understand that they are the party, and that the situation is the party. Whereas in other places, people show up and expect to be told where the fun is. We were a lusty group, and we just loved playing music. It was a celebratory thing. We didn’t have to play music to get laid, so we played music to have fun. We were up for anything, and people in New Orleans got that.

Vicki Peterson: At the time we finished the Vermilion album in 1998, I remember thinking that the whole Americana scene and the alt-folk-country thing was starting to become commercial, or potentially commercial. So I thought, “OK, maybe we can be the successful Americana band.” But then Wilco exploded, so they got to be the successful Americana band.

Peter Holsapple: I think I kind of jammed the Fairport Convention stuff down everybody’s throat at first. Carlo referred to it at one point as “leprechaun music,” so I’m not sure that he was on board with it, but we did the bulk of our Fairport stuff after he left the group. I’ve been listening to Fairport and Richard Thompson since ninth grade, and all of those songs mean so much to me.

Vicki Peterson: Fairport Convention was one of many musical worlds that I was introduced to by the Drifters, and there was most definitely a big Fairport/Drifters connection, which was cemented when we had the opportunity to do a few shows with Iain Matthews as an honorary Drifter. That, and the beautiful, expansive show that Peter steered at St. Ann’s Church in New York, when we performed Sandy Denny songs with a variety of guest singers. That was one of the best and worst nights of my musical life; all this incredible music, the Drifters as house band—and I had bronchitis and a 102-degree fever that left me sounding like Maurice Chevalier.

Peter Holsapple: Most of the Listen, Listen EP was from a German radio broadcast that happened pretty spontaneously. Except for the title track, which was recorded at Ground Floor Studios in Chalmette, Louisiana with Mike Mayeux at the board. That’s the last song the Drifters ever recorded.

Mark Walton: This version of “Meet on the Ledge” is different from the one on the Listen, Listen EP. It’s a full-band studio version from the very first session we did when Russ joined the band. The live version of “I’m A Dreamer” is from the St. Ann’s show.

Susan Cowsill: The Continental Drifters came at exactly the right time for just about everybody who was ever in it. Everybody was coming out of something, musically or personally. We were the Island of Misfit Toys, and we gravitated toward one another’s maladies and healed each other as best we could.

Peter Holsapple: It certainly came at the right time for me. The end of the dB’s had been so unsubstantial, and I left R.E.M. with a bad taste in my mouth, although in both cases everybody’s pals again. I needed something really uplifting, and the Drifters really provided that. The dynamics of the Drifters were so different from every other band I’d ever been in, and that was exhilarating. It would also be fair to say that the Drifters was a band full of strong-willed individuals, and it was my first real exposure to people screaming at each other. The Drifters were all very confrontational with each other, and most of the band members came from families that communicated that way. I felt a little shell-shocked at my first few band meetings. But the other side of the coin is the love and camaraderie that we had, and how we all hung out and had a good time singing and playing together and enjoying each other’s company, and how we became a family unit. No matter who was in the band at any given time, that feeling was always there.

Vicki Peterson: One of my earliest and most potent Drifters memories was in the kitchen of Raji’s. I think that this was before I even joined the band. They were working on the harmony of a song that they had just written that afternoon. We sat in the kitchen, and I was surrounded by Gary and Mark and Ray and Carlo and Peter and Susan, and it was like being inside this incredible storm of voices and music. That was the moment that I realized that this was healing to me, and that it was where I wanted to be.

Susan Cowsill: Everything about being in the Drifters was inspiring. I started to play guitar and started to write songs because I was in the Drifters. I’d come up with my brothers in our family band, but my brothers weren’t out to nurture their little sister as a songwriter or a singer. But with the Drifters, it was ‘Give it a try, see if you can do it,’ and they made me feel comfortable doing that. The Cowsills is a beautiful ride, but it’s just one ride. The Drifters was like being at a freaking carnival and riding every ride. We had every crayon in the box.

Peter Holsapple: The great thing about every version of the Drifters is how the pieces all fell together so naturally and so correctly. That became even more so after the girls joined the band, because suddenly we had this large group of people from all these different walks of music, yet it all coalesced so well. It was our desire to make it work, and to do the best for each other’s songs that we could do, and it felt great.

Robert Maché: Six people on stage, all in the same space and laughing their asses off. How often do you get that? When it was good, it was like a careening van with six dogs sticking their heads out the window with their tongues wagging.

Peter Holsapple: At times, it felt like the band was a huge locomotive, and the velocity could get to insane levels, but you wanted to hang on because it was thrilling. There were nights when I felt like I was in the best band ever, period, end of story. There would be times when we’d get through a song and somebody had just pulled off something miraculous, and you’re standing there at the end of the song looking around at everybody and thinking, “How did we just do that?” Those moments just lifted you off the ground, and they happened on a regular basis. It was everything I had ever wanted in a band—musicianship, camaraderie, love, harmony, and alcohol—and I’m grateful for the experience.

Robert Maché: The Drifters never had a leader, which was a great thing in a lot of ways but which could drive record-company people crazy.

Susan Cowsill: This band was allergic to preparation. Whenever we tried to plan ahead, bad things happened. We opted out of finding some machine to process us through, or to guide us. All these structured little establishments of record companies and people’s ideas of how we should be, we rebelled against all of that. When we signed with Razor & Tie, they talked about getting us to make a hit single, or putting the girls up front. When those thought processes started to invade our little island, it was like the planets started to realign, or unalign.

Peter Holsapple: Being in the band was a remarkable, visceral experience. Even when it got to the point where people were having fights with each other, we could ride up over that, and use that to fuel the engine somehow. The Continental Drifters started with comparatively modest goals of playing music together and having a good time doing that. It eventually succumbed to some of the necessities of being in the music business. But overall, it was a lovely experience when everything was working right. And when everything wasn’t working right, the music was still really good.

Susan Cowsill: The Drifters took me to places that I’d never imagined going, and it was beautiful from beginning to end. Even at the end, when things started to get a little weird on the personal side, we didn’t let it affect the music. The gory details are always gonna be the gory details, and nobody goes out without some drama. But as a band, I don’t think we ever did anything to embarrass ourselves. We had to go to our own corners for a while, but that’s life, and that stuff passes. The Continental Drifters was a pretty love-based operation, and in the long run, we’re still each other’s best friends.

Robert Maché: The reunion show we did at Carrollton Station in 2009 was awesome. It was a mess, but it was beautiful. It was like we were right back at Raji’s. We didn’t know what was happening, but it was amazing. We did one rehearsal at Susan and Russ’ place, and mostly just called out song titles and said “Oh yeah, I remember that.” Other than that, the rehearsal was mostly just laughing and telling stories. And the few songs we did rehearse, we fucked up, because we were laughing so hard.

Susan Cowsill: The combination of human beings in the Drifters was just one of those magical things, and that chemistry was able to morph around as the band changed. I personally attribute it to us having been together in past lives. I think we go around with the same tribe over and over again, and that our comfortability and familiarity with each other comes from having done this before. I don’t know what our mission was the last time, but the ease and familiarity that we had with each other was kind of mystical. We were souls entwined.

Carlo Nuccio: What’s real about all of this is that we all loved each other so fuckin’ much, and we still do. That love came out in the music we made, and I think you can hear that.